In the intricate dance of evolution, nature has perfected movements that are both efficient and awe-inspiring. The study of animal locomotion has long fascinated scientists and engineers, leading to a field known as biomimicry—where human innovation draws inspiration from biological systems. From the blistering sprint of the cheetah to the peculiar sideways scuttle of the crab, each movement tells a story of adaptation and survival. These natural marvels are not just curiosities; they are blueprints for advancements in robotics, transportation, and even medical devices.

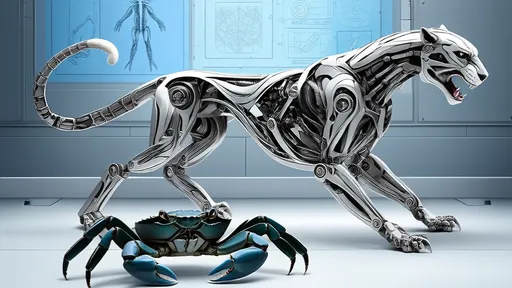

The cheetah, renowned as the fastest land animal, embodies speed and agility. Its ability to accelerate from 0 to 60 miles per hour in mere seconds is a feat that has captivated researchers for decades. The secret lies in its flexible spine, which acts like a spring, storing and releasing energy with each bound. Its large nasal passages and heart facilitate rapid oxygen intake, fueling its muscles during high-speed chases. Moreover, the cheetah's non-retractable claws provide exceptional grip, akin to soccer cleats, allowing it to maintain traction on varied terrains. This combination of biomechanical advantages has inspired developments in robotics, such as Boston Dynamics' WildCat, which mimics the galloping gait of big cats for enhanced mobility in rough environments.

Transitioning from the savannah to the ocean, the movement of marine animals offers another rich vein of inspiration. Take the jellyfish, for instance: its pulsating motion, driven by rhythmic contractions of its bell-shaped body, is a model of energy efficiency. Researchers have created soft robots that emulate this movement, capable of navigating delicate ecosystems without causing damage. These robots could revolutionize underwater exploration or even perform minimally invasive surgeries. Similarly, the undulating motion of eels and fish has informed the design of underwater vehicles, making them quieter and more maneuverable than traditional propeller-driven models.

On land, the crab presents a fascinating case study in unconventional locomotion. Unlike most animals that move forward, crabs exhibit a lateral walk, driven by their specialized leg joints and robust exoskeletons. This sideways scuttle is not a limitation but an adaptation to their often cramped and complex environments, such as rocky shores or coral reefs. It allows them to quickly evade predators and navigate tight spaces with ease. Engineers have looked to this movement for designing robots intended for search-and-rescue operations in collapsed buildings or disaster zones, where traditional wheeled or legged robots might struggle. The crab-inspired robots can shimmy through rubble, providing critical assistance where humans cannot reach.

Birds, too, contribute invaluable insights. The albatross, with its majestic gliding over oceans, utilizes dynamic soaring to travel vast distances with minimal energy expenditure. By harnessing wind gradients just above the water's surface, it can stay aloft for hours without flapping its wings. This principle has been applied to unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), enabling them to conduct long-duration surveillance or environmental monitoring missions with reduced power consumption. Similarly, the precise hovering of hummingbirds, achieved through rapid wing beats and unique joint mechanics, has inspired micro-drones capable of stable flight in turbulent conditions.

Even insects, often overlooked, are masters of movement. The flea's incredible jumping ability, powered by a protein called resilin that acts like a rubber band, has led to advancements in materials science. Synthetic versions of resilin are being used to create more durable and responsive prosthetics. Ants, with their coordinated carrying of heavy loads relative to their size, have influenced algorithms for swarm robotics, where multiple small robots work together to accomplish tasks too large for a single unit.

The application of biomimicry extends beyond robotics into everyday technology. For example, the study of shark skin, which is covered in microscopic ridges called denticles that reduce drag, has led to the development of faster swimsuits and more efficient coatings for ships and aircraft. This not only improves speed but also significantly cuts down on energy consumption, highlighting how nature's designs can promote sustainability.

In the medical field, understanding the movement of snakes—which use scales and muscular contractions to grip surfaces—has aided in creating endoscopic devices that can navigate the intricate pathways of the human body with minimal invasion. Similarly, the way geckos adhere to walls through van der Waals forces has sparked innovation in adhesive technologies, leading to tapes that can hold substantial weight without leaving residue.

As research progresses, the line between biology and engineering continues to blur. Scientists are now using advanced technologies like 3D printing and AI simulation to decode and replicate these natural movements with unprecedented accuracy. For instance, by studying the joint kinematics of a cockroach, researchers have developed robots that can traverse unstable surfaces, potentially aiding in exploration on other planets.

Ultimately, the journey from cheetah sprint to crab walk underscores a profound truth: nature is the ultimate innovator. Each animal's movement is a solution refined over millennia, offering lessons in efficiency, adaptability, and resilience. By looking to the animal kingdom, we not only advance technology but also foster a deeper appreciation for the wonders of the natural world. As we continue to face global challenges like climate change and resource scarcity, these biomimetic innovations may hold the key to sustainable progress, reminding us that sometimes, the best way forward is to observe and learn from the life around us.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025